Care grounds you. Challenge stretches you. Growth requires both.

Most culture challenges are puzzles—not because they're mysterious, but because they're human. And human systems don't respond to single levers the way computers or machines do.

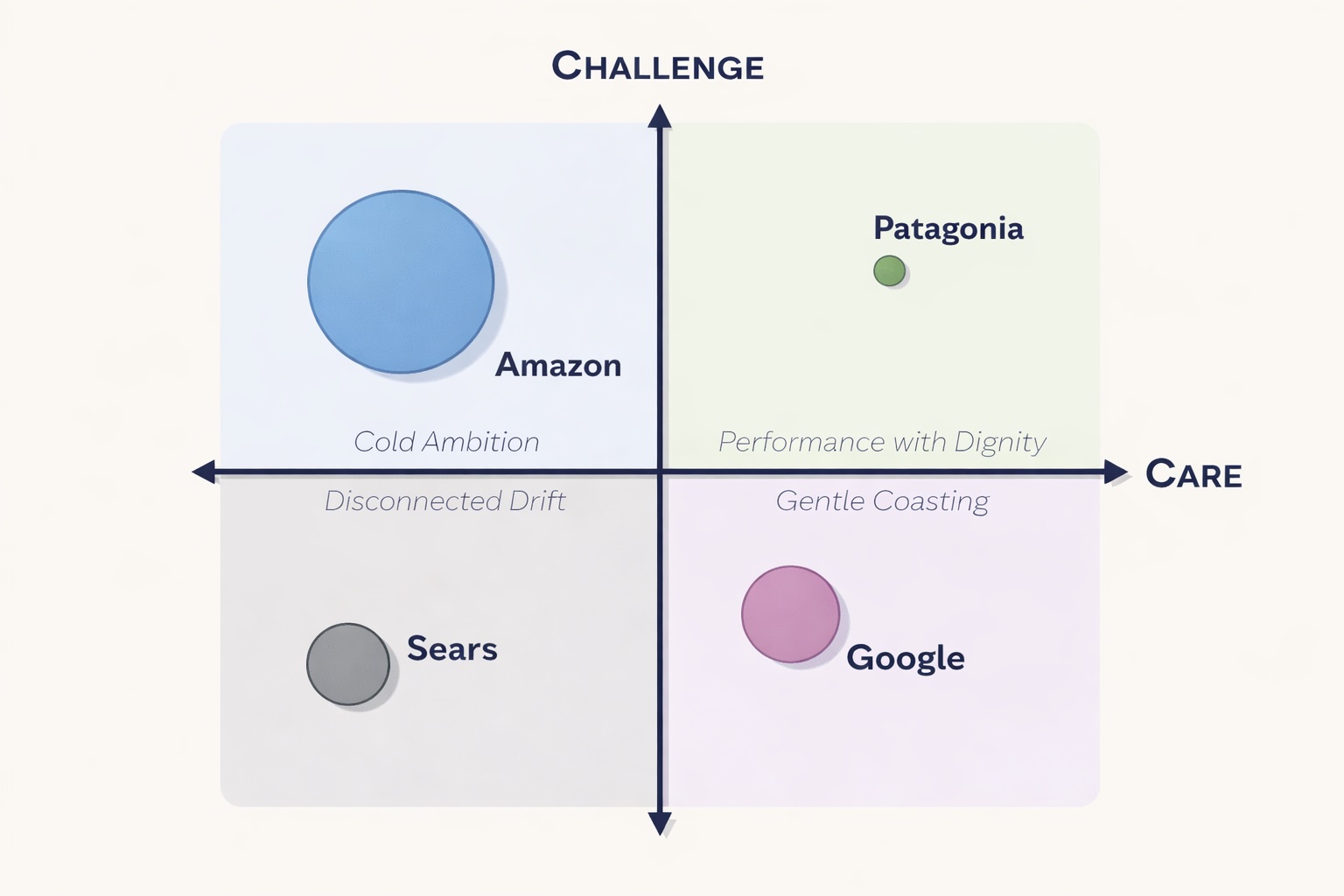

After more than a decade assessing organisational cultures, we developed a model to make sense of the recurring patterns behind those puzzles. We call it the Care–Challenge Framework.

It starts with a straightforward idea: organisational cultures work best when they are both deeply caring and deeply challenging, in equal measure. This is rooted in developmental psychology: people tend to learn and adapt best in environments that are "safe enough and demanding enough" (Kegan and Lahey). Care meets the core human need for safety, trust, and belonging; challenge meets the core need for growth, agency, and competence.

In other words, a healthy culture sends its people two messages at once:

-

We have your back.

-

And we expect your best.

Most culture challenges become easier when viewed through this lens. Here's an example.

A familiar puzzle (and why it matters)

A Head of HR at a leading software company once shared a difficulty that I've heard in different forms over the years:

"People here feel safe. We've invested in wellbeing. Psychological safety is strong. What I don't understand is... why aren't people bringing new ideas?"

This is a great puzzle because psychological safety is widely viewed as the unlock for speaking up and innovation. And it is important. But it also illustrates a broader point: no single cultural ingredient delivers on its promise in isolation.

In this example, psychological safety is only half of the equation

Psychological safety is what we call a care signal. It reduces fear, lowers interpersonal risk, and makes it easier for people to speak up without worrying they'll be punished, humiliated, or ostracised. In other words, it sends the message: "You belong here. You matter. We want to listen to you. We've got your back."

But safety and the absence of fear doesn't automatically produce initiative, candour, courage, or creativity. For that, people also need a reason to stretch. They need a sense that it matters, that standards are real, that there is a meaningful goal worth reaching, and that the organisation expects them to bring their best.

Challenge signals create that stretch—clear standards, direct feedback, accountability, and ambition. Without them as a counterbalance, even strong care signals like psychological safety can fall short of their promise. Instead of more speaking up, you can inadvertently get more silence.

Care and safety help people speak up. Challenge gives them a reason to.

And as the world's foremost expert on psychological safety, Amy Edmondson, has noted: organisations can mistakenly do the "nice" part of psychological safety without building the additional norms that make it useful in practice.

The Care–Challenge framework applies to the entire culture

This model applies not only to individual cultural elements—like psychological safety and accountability—but to whole organisational cultures.

When a culture is high on care but low on challenge, the environment can feel warm and safe—yet slowly slide into drift: missed commitments, softened standards, low accountability, and fewer hard conversations. Not because people lack capability, but because the system doesn't create enough stretch. In low-demand environments, a predictable human pattern emerges: people optimise for comfort, conserve effort, and default to familiar routines. That isn't laziness; it's an understandable response to the signals around them.

Similarly, when a culture is high on challenge but low on care, the environment can feel sharp and high-performing—yet gradually tip into strain: burnout, fear, internal competition, brittle collaboration, and thinning trust. Not because people are unkind, but because the system doesn't provide enough support to sustain the pressure it generates. In high-pressure environments, another predictable human pattern emerges: people protect themselves, narrow their focus, and rely less on others. That isn't a character flaw; it's what happens when demand outpaces support.

Our clients tend to adopt the care–challenge language right away: "We're high care, low challenge." "We're high challenge, low care." "We need to rebalance." The model makes something as complex as culture feel graspable and actionable.

A practical takeaway

Strong challenge signals—like ambitious targets, high standards, and results focus—need strong care signals to balance them: recognition, belonging, empowerment, and support. And the reverse is also true: strong care without sufficient challenge often creates a culture that feels good and safe, but slowly loses its edge.

The goal isn't "more care" or "more challenge" in the abstract. It's the right balance—in your context—and knowing which dial to turn when.

What's next in this series

In the next few posts, we'll make this practical by defining what "care" and "challenge" look like at the organisational level, and mapping the four common culture profiles that show up when the balance shifts. From there, we'll explore how leaders can add more challenge or more care to their cultures, without losing the best elements of either.